In Ethiopia, children generally learn in their mother tongue from grades 1-4, before teachers switch to teaching exclusively in English in grade 5. This is common where there are many local languages spoken and English is seen as a route into further education, or as a neutral language which doesn’t favour any specific group of people. In Wolaita Zone, SNNPR home to Link’s girls’ education project, the first language for almost all girls is Wolaytatto.

Evaluation data from the project shows quite a complex language environment when it comes to learning. Very few girls speak English at home whilst almost 100% speak Wolaytatto, and there are no books, media or newspapers in English available locally. This means that girls have little exposure to English apart from what they are taught in school, making the switch to English in grade 5 particularly challenging. According to our findings, just 27% of girls in one sample district feel comfortable learning in English.

Language as a barrier

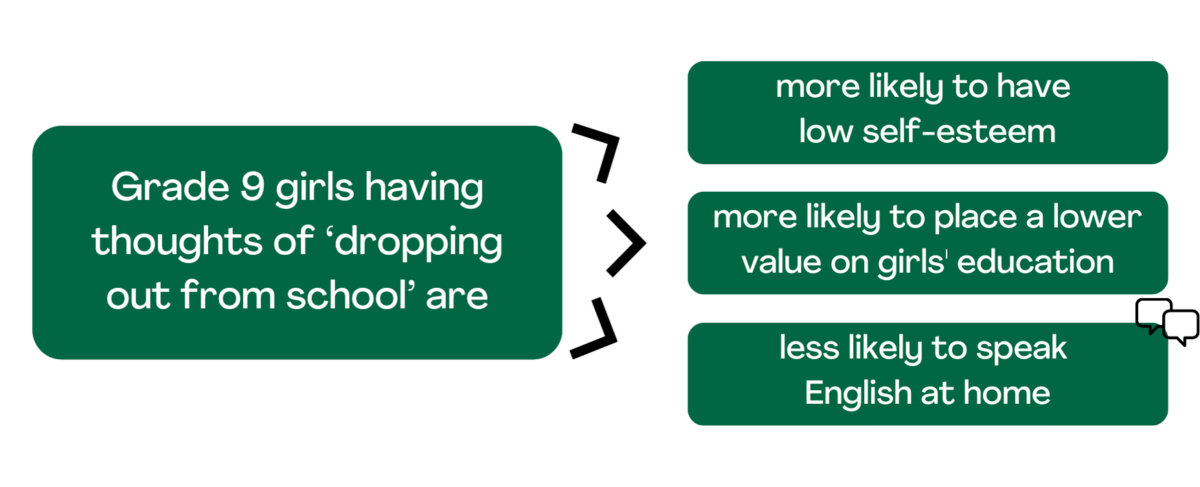

Girls in primary grade 7 and secondary grade 9 linked the language used in schools to thoughts of dropping out early. They have also highlighted language to be a barrier to attending school, staying enrolled in school, and to transitioning through the different levels of education. This data is very important to understand and reduce the barriers that stop girls attending and learning at school.

The data raises further questions, however. 92% of girls in Damot Pulasa district highlight language to be a factor in school drop out and yet in Kindo Koisha, the most remote of our districts, only 23% reported this. In Damot Woide district, the numbers dropped to 0%, but 40% of students there said they see proficiency in English as important to staying enrolled in school.

Language and other barriers

The evaluation findings also show that language melds with other barriers that girls face, such as low self-esteem, responsibility for household chores, or low expectations of them, creating layer upon layer of obstacles that they have to navigate.

What the teachers say

Asked to select key barriers to education for girls in Link supported schools, over 90% and 70% of male and female teachers respectively selected language alongside common barriers for girls such as poor school infrastructure, lack of female loos, long distances to school, lack of water supply, and the quality of education provided.

What Link is doing

Since 2014, Link has supported language and literacy in schools. Initially, we focused on English language competency for teachers of upper grades, more recently expanding to Wolaytatto competency training for teachers of grades 1-4 to strengthen students’ literacy foundations before switching to English in grade 5. We supported the development of materials for teacher training and follow-up by school supervisors based on a needs assessment to determine what training content would be most useful in local contexts. All materials integrate teaching methodologies which consider gender and inclusion, safeguarding, and use social and emotional learning approaches to boost girls’ confidence in learning.

Our reporting has given us much useful information on language. It confirms that there are clear linkages between the language students are taught in and attendance, transition between grades, drop out and retention, and that language interacts with other barriers that girls face. We intend to deepen this understanding through our monitoring data and upcoming mid-project evaluations to provide a basis for adaptations in the final three years of the project.

Worldwide, education related institutions are increasingly of the opinion that learners should be taught in a language that they understand, with research across sub-Saharan Africa showing that learning in English or another dominant language has a negative impact on children’s classroom experiences and results, particularly for pupils from marginalised communities. Learning from projects like ours provides additional evidence to support this call, whilst also recognising that language and education is complex, and inexorably wrapped up in identity and culture.